NEWS

Interview: Cover Artist, Michael Gillette

BECOME A FLEMING INSIDER > JOIN HERE

Interview: Cover Artist, Michael Gillette

Posted on 17 July, 2025

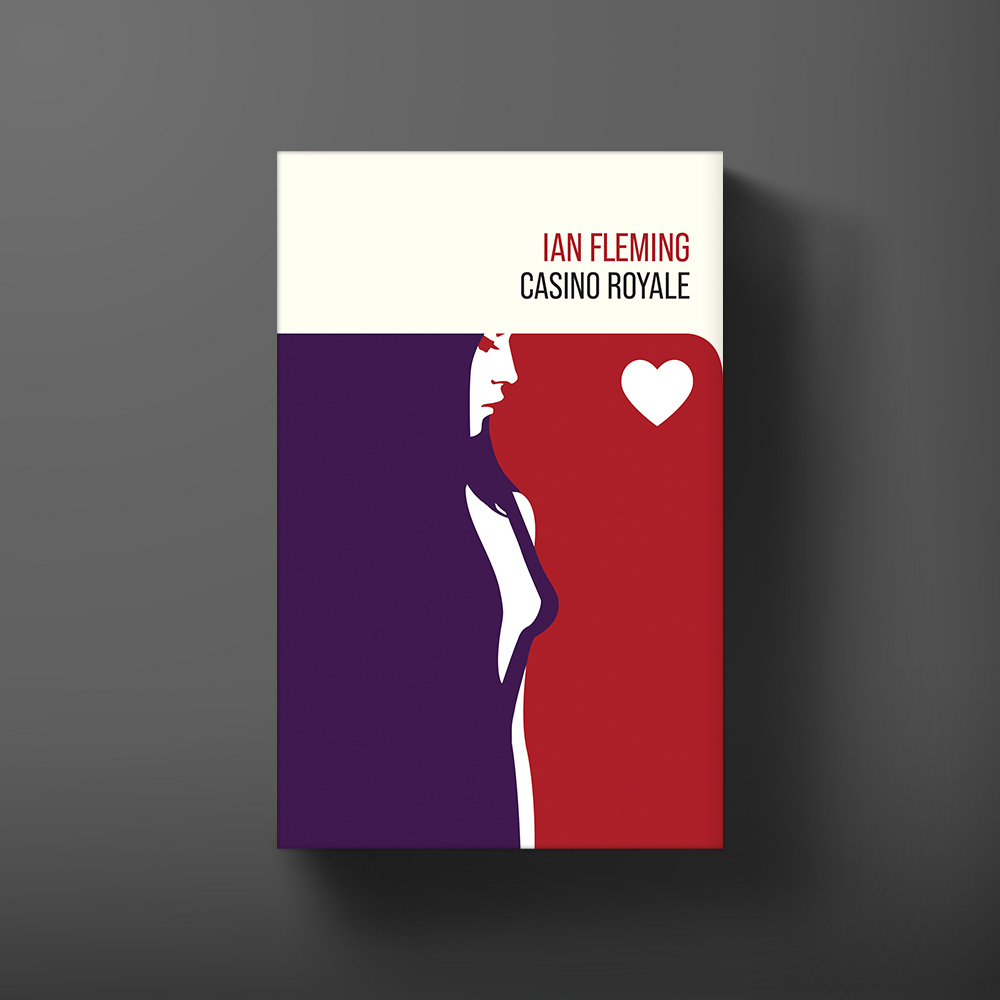

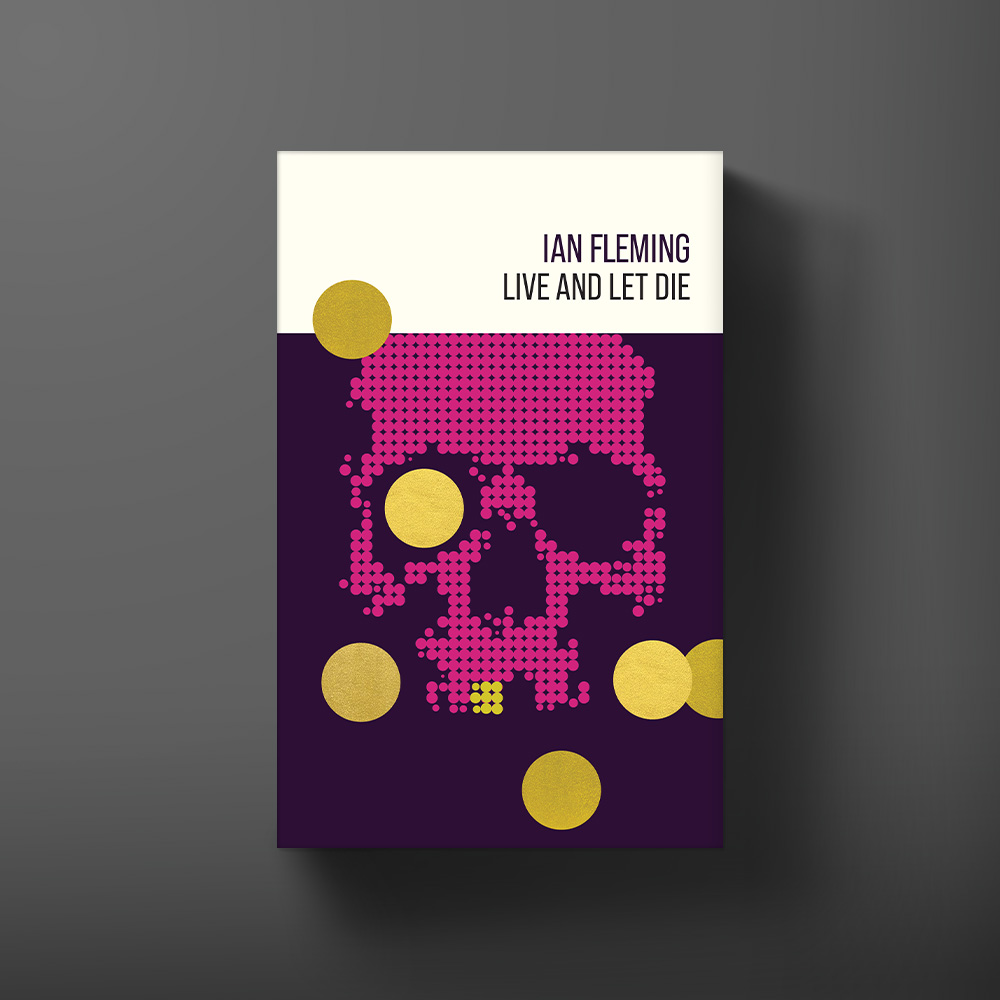

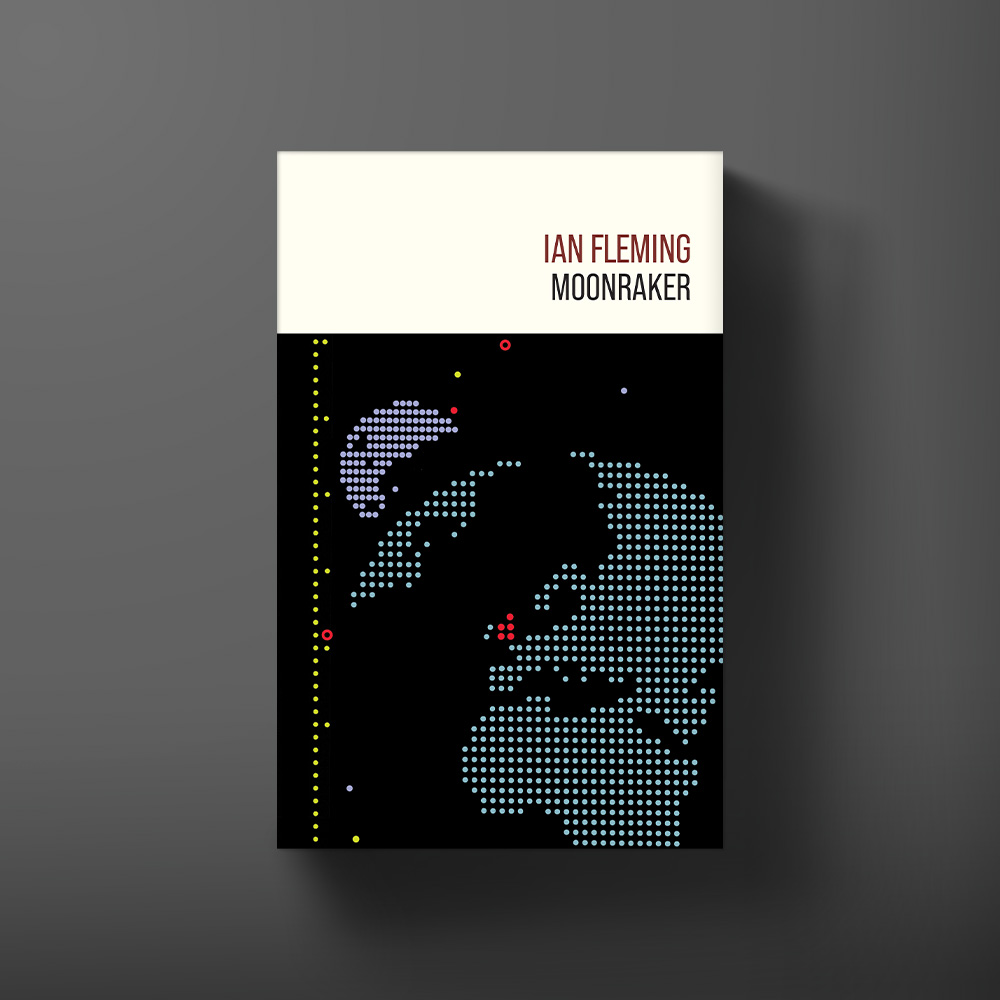

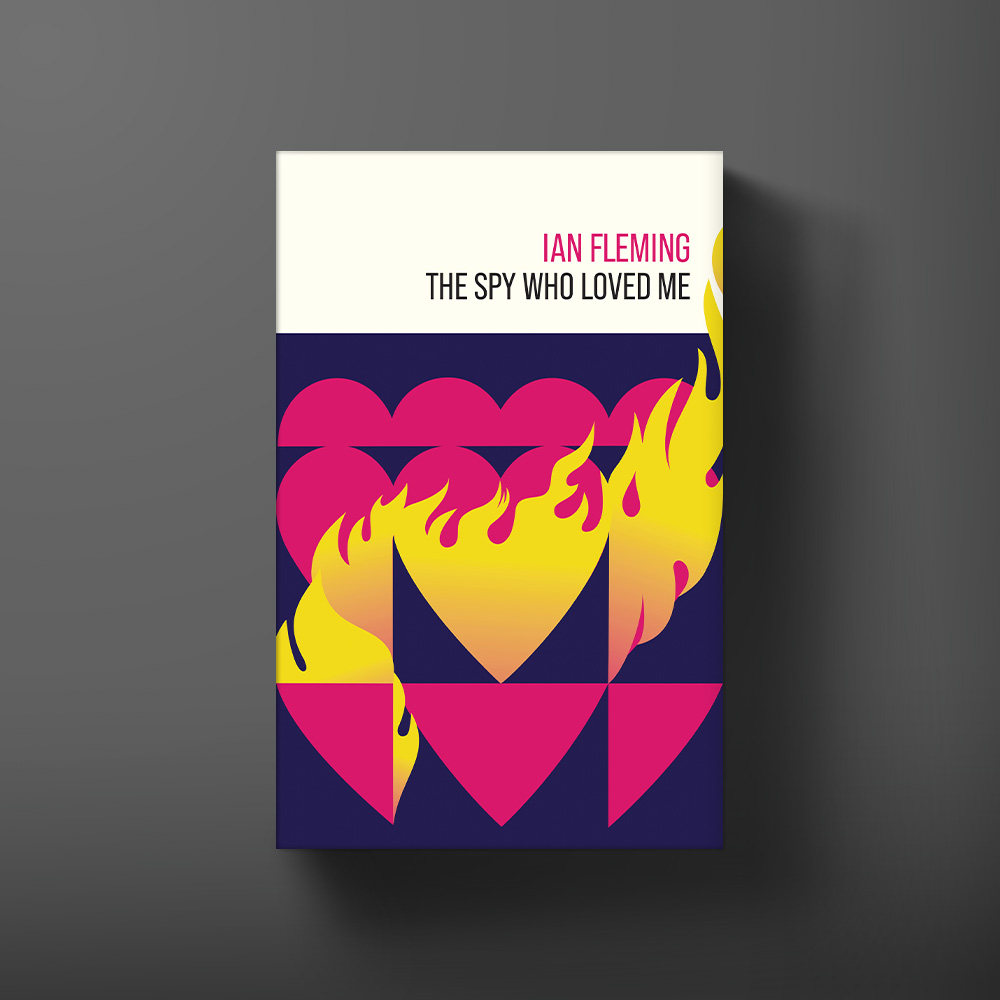

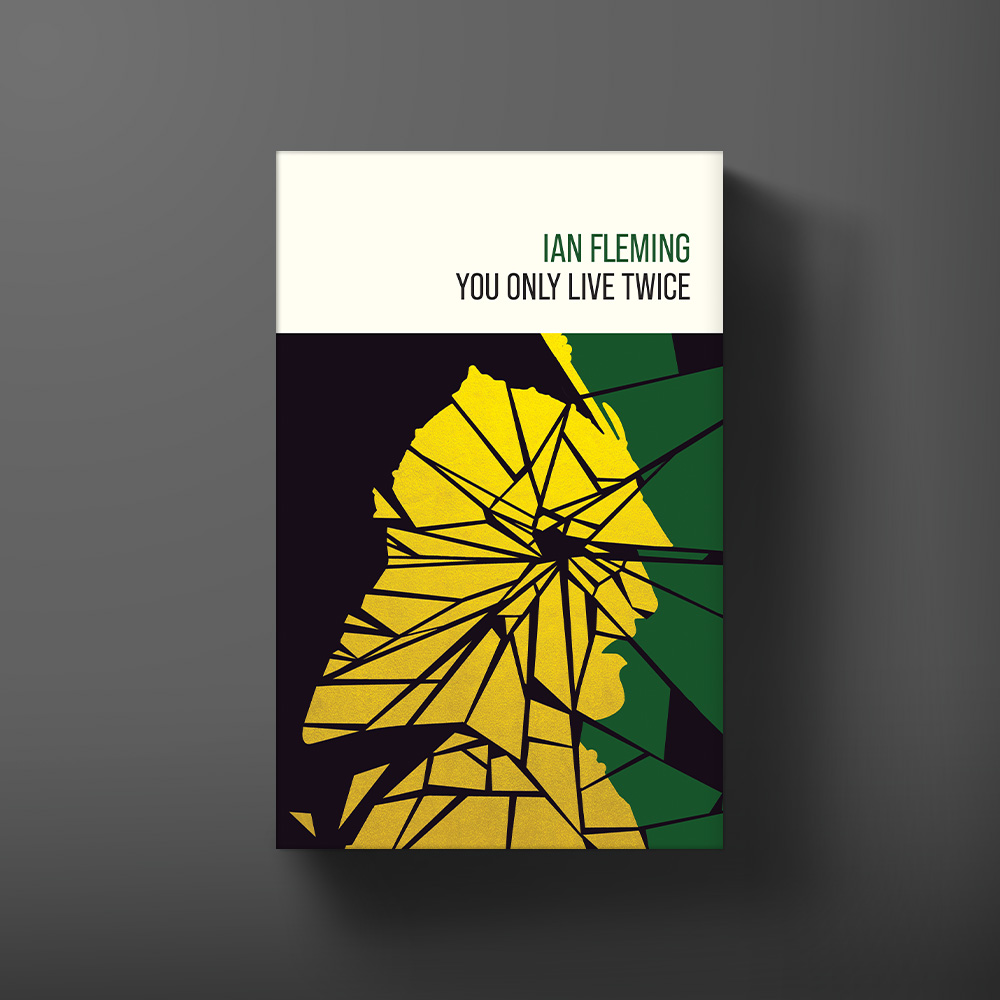

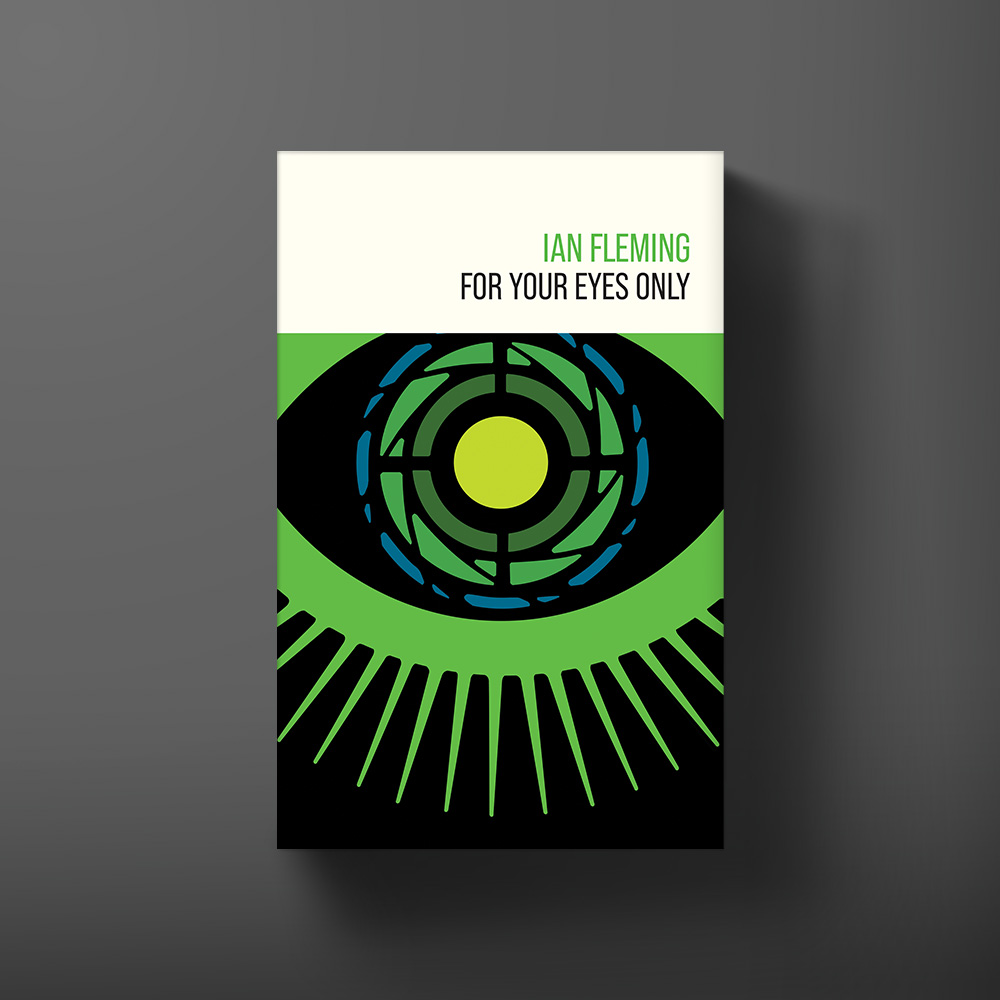

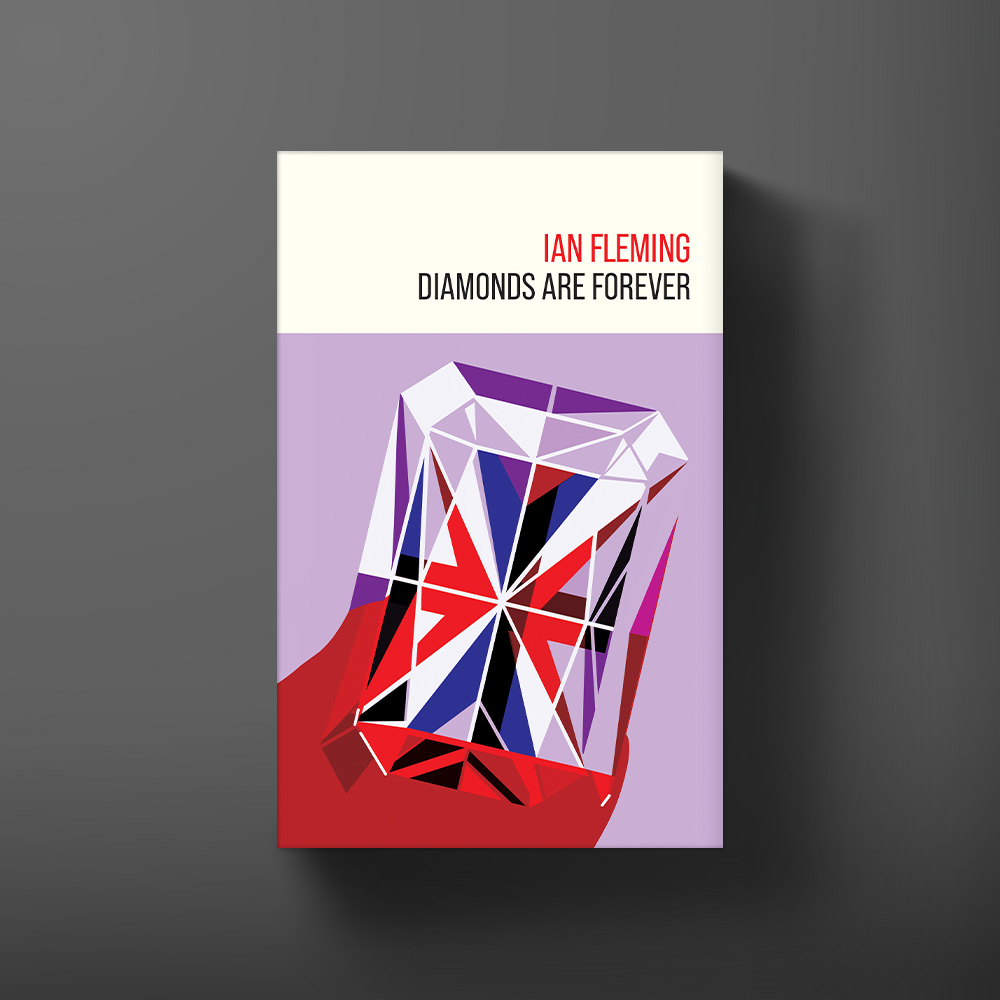

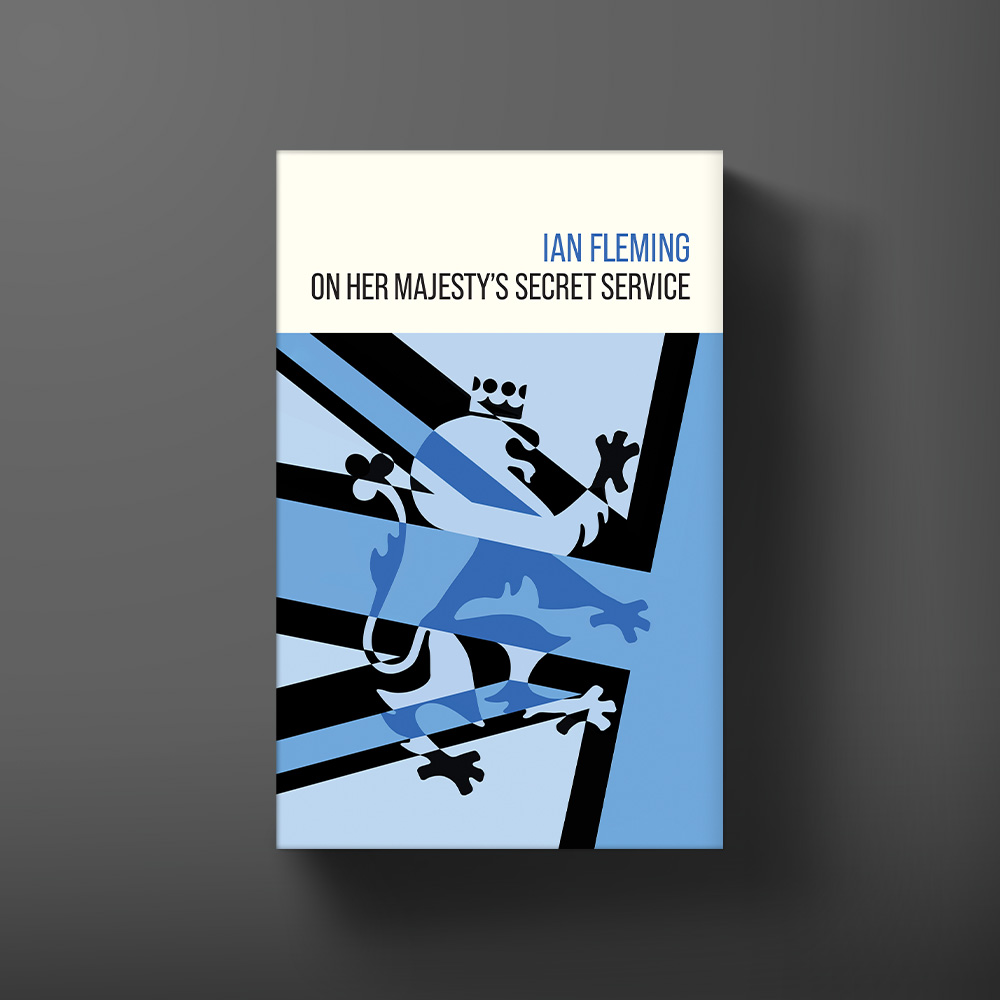

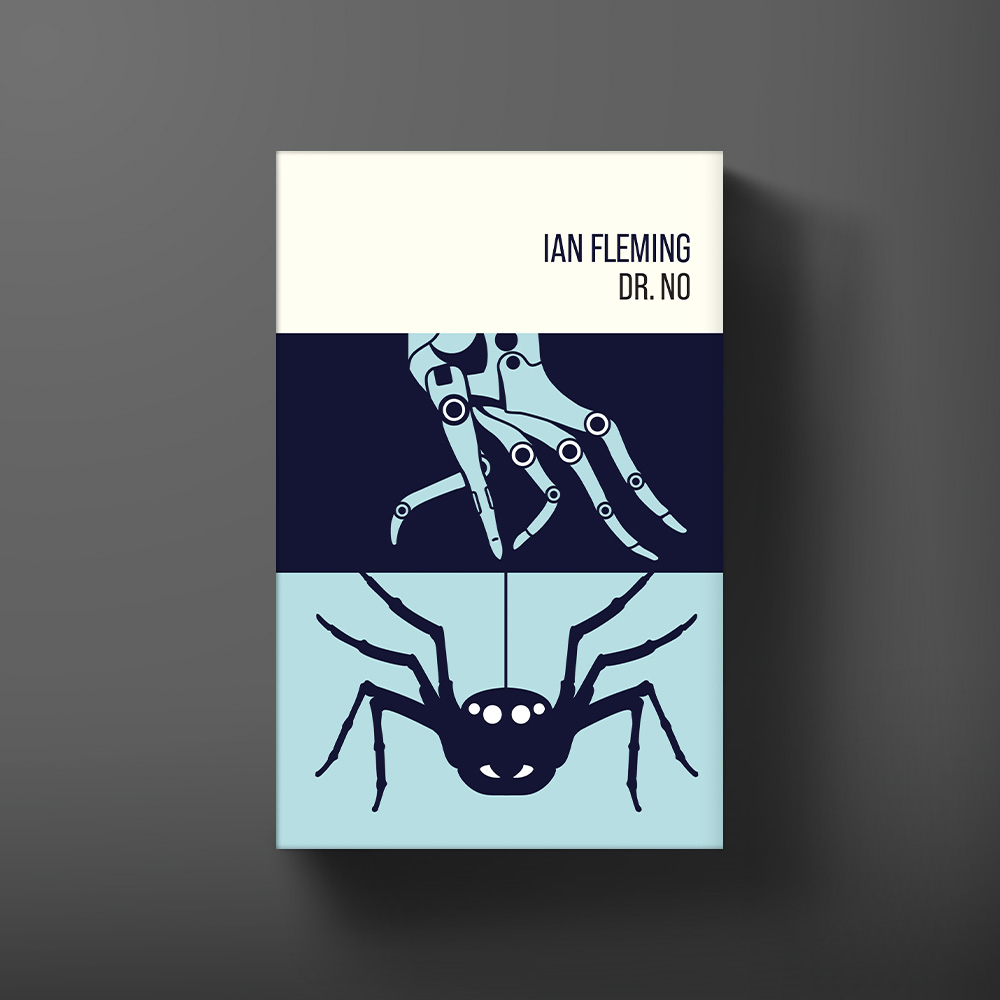

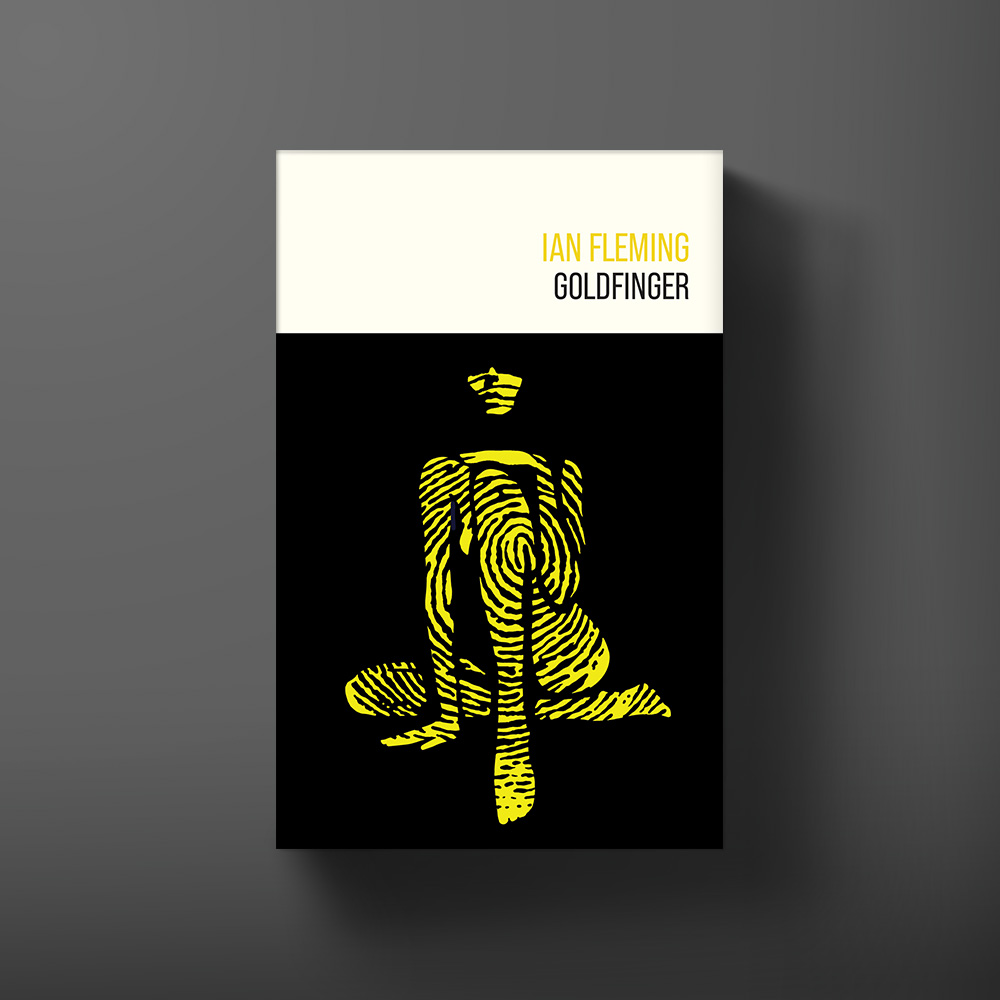

We sit down with Michael Gillette, the man behind the colourful James Bond hardback editions.

How did it feel to collaborate to build on Fleming’s 007 legacy with us at the start of our self-publishing journey?

2018 was when I first had the idea to pitch these designs. I felt like it was inevitable that you would self-publish the books. I’m not sure you’d even decided to at that point [we hadn’t!] so I don’t know why I was so convinced. I had the idea for something really geometric, simple, bright and bold which hadn’t been done, that I could recall. I’m really glad you’re self-publishing. In the shifting sands, it’s the right thing to do. And I know it’s a massive venture. I started out doing sleeves for indie bands, and it feels a bit like that. Being part of a smaller unit, you’re much more part of the endeavor, and you want it to succeed. I want the books to succeed and I want you folks at Ian Fleming Publications to succeed.

I view my career as a rodeo illustrator. Certainly when I did the centenary editions, I was right in the middle of doing a million other jobs. And obviously, I never had any dealings with The Ian Fleming Estate then, just a shadowy missive every now and again that would come through Penguin. You don’t really build a relationship, you do the job and then it’s off and gone. It’s been really interesting to get to know you all, to see how it works, and to watch your progress too. I don’t want to conflate my experience with everyone’s experience, but it seems as things get more and more virtual, the relationships that sustain are the real world relationships. That’s the way I feel. It seems like The Estate has always been a bit like that anyway – more about direct relationships and for sure, it’s hard to get into, but it is loyal once you are in there.

There was no doubt that these books had to be designed by someone who understood the Bond book world. Do you think these new circumstances had an effect on the designs and the design process?

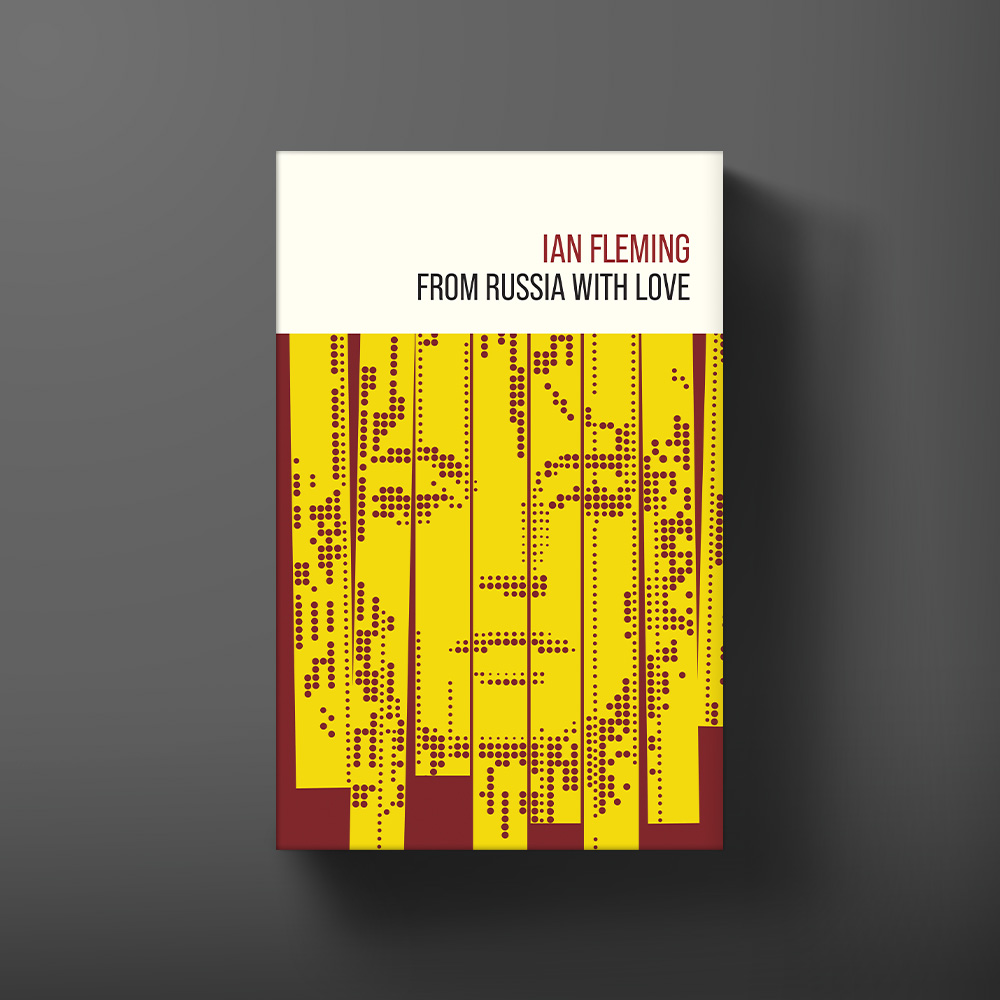

Yes definitely. At Penguin, there was a whole marketing department, a designer and an art director, John Hamilton, a legend. It did go very smoothly, but you’re being presented with something and told what to do. Even though it’s what everyone sees first, the artist is generally hired last. They know what they want, and then they pick an illustrator to do it. This project was completely the opposite, it was self-initiated. I could do anything I wanted, certainly to begin with. Take From Russia with Love. You’d already approved a different idea, but I thought this was better.

Does that extra flexibility facilitate your creative process? Do you wait for the flash of inspiration or do you go looking for it?

Well, initially the ideas came in a flood. I did this very geometric burst to begin with and then I just put them away until 2021. I was teaching a class on concept illustration which includes things like negative space and symbolism. I’d say to the students ‘your mind will give you as many solutions as you ask of it,’ which sounds ridiculous, but it’s actually true. Most people only ask for one idea, or ask for a couple of ideas, and then get very stuck. At the end of that class, I had a lull because Covid was still strong in California, so I took another two weeks. I had these ideas that were based on what I’d been teaching and showing the students, these graphic concepts. The designers I introduced them to were people like Saul Bass, and those ideas were absorbed into them too. So I did another two week burst of that, and then put them away again. I thought I could just be doing it forever.

I guess it’s just trying to keep things fresh. I teach my students that your subconscious is where all the ideas are, and your conscious is, you know, the little peak on the mountain, above the sea, and all the ideas that are going on underneath it, you just have to keep asking for them. If I got really stuck with an idea, I’d go back and read the book just to try and find a new direction on it. The other difference of this job is just how long it went on. I’ve never had anything go on this long. It’s been six years and I couldn’t show anybody at any point, apart from maybe my wife, who is a good sounding board.

With From Russia with Love, for example, there were at least four versions which are all very similar. Do you think a design improves the more times you do it, or can you overdo it?

Oh, you can kill something by over-polishing it. That one is a bit different, because it was a technical difficulty. I had an idea which I couldn’t find an easy way of executing. I could get it approximated quite quickly but making the image read without the face getting wider or distorted took a lot of shifting of dots by hand. It might have been a day and a half’s worth of shifting small dots to make it right. I’d spent so long getting it to try and work, and realizing that it was working, that I probably did ‘white knuckle’ it a bit and say, ‘no, this is the idea.’

Why were you insistent that we went with this cover in particular?

Because it’s an idea that I think is absolutely right for the book. It suits the story of the book. The two lures of the story are the cipher machine and the love interest. For those things to be married together in a single image with just two colors, it just works. Saul Bass is about symbolizing and summarizing. And that’s exactly what this cover does. I suppose there’s a point at which you’ve spent so much time on something that you will not let it go. Your mind has become shrunk to that idea. It’s like you’ve become a stalker for your own idea. I think that’s the only one that I really felt like that about. It was a good call. Well, it was a call.

The design process for these books was more like creating an object than just a cover. What did you learn from this?

With the 2008 books, I didn’t see them until they were physical products. Apart from the cover, I had no idea what the rest of it was. When I left college, I started designing for bands. That was my USP. I really loved it. I stopped because my illustration career took over, but I’ve always been into the idea of the total look of something. To be able to have that total look really excites me. I think that at this point in time to make a physical book, especially a beautiful hardback, there’s got to be a level of thought behind it that’s worth people buying it. You just think, ‘how does this look in the hand?’ That’s why I tried to make things look as close to the size they would be, like the bullets.

I’m not saying it’s a dying art, I think it’s just that designers are dying off because they can’t afford to do it as a job. You go into Waterstones and everything looks very much the same, the same typeface and the same treatment. With the self-publishing, you’ve done something more considered.

The endpapers really add to this. How did you go about making them?

I’ve got this sketchbook with lots of ideas, where I would just draw endlessly, like a bank of ideas. I always tell my students to use their sketchbooks. Draw, draw, draw. Sketch it out. You never know what you’re going to get. The muse comes when you’ve got a pencil in your hand. I couldn’t understand how I was still coming up with ideas, but they were working. Sometimes, the more ideas you’re having, the more ideas they have. I don’t know how it works, but that’s how it works.

Many of them are like optical illusions. This must have been fiddly and time-consuming?

They’re techniques I taught at college: concept art and digital design. So I know how to manipulate things that way and make them repeat. Sometimes they work and sometimes they don’t. Like for Thunderball with the silencer that almost looks like a crucifix – that’s a motif that worked really well. I was amazed at how I was still doing all the endpapers right down to the wire. It takes a long time. I want to give some value for money there. I know the expectancy of being a fan of something and the disappointment when it’s shabbily treated. I want to speak to that in the Bond world.

For the centenary editions, you decided not to use any guns. Why was that and what was different for these editions?

We just don’t want to glamorise guns, really. They’re still not gun heavy but they just work so well. I feel they draw on the action of the books a lot more than the previous covers. If there was a big wheel of things, this series draws on them: gadgets, some girls, some guns, some death, some bombs… The whole world of it has become so iconic that it’s so much fun to play around with that stuff. I’m not reinventing the wheel, just putting some good rims on it, trying to combine things in a new way to make you see them slightly differently. It’s so much fun just to play around with that stuff, it’s why everybody loves James Bond.

The wheel is a great analogy. The designs draw on so many elements, but then they feel cohesive at the same time. Was this hard to achieve?

That is the difficult thing to pull off. When I was at college, I could make really good images of things, but I could never make a second one the same. I couldn’t make a cohesive series of things, which is a bit like where AI is currently at. It can’t make a cohesive set of ideas. It’s taken me a long time to be able to pull that manoeuvre off. I do sometimes wonder how long it will be before AI makes that leap.

I try to ask myself, ‘what is a human response to this?’ Is this natural or is this synthetic? Leonardo da Vinci said that 98% of people create nothing but excrement. A lot of work that I’ve done wasn’t very good, but I was sharpening the axe to do something which was good.

What are you doing in your work to combat these fears? What would you teach to your students?

Look at Ian Fleming, he didn’t wait for the muse. He went on holiday and then bombed them out. But they’ve endured somehow. Something went on those pages that’s well beyond what you could ask a machine for. And I think it’s his complicated human nature that’s connected with people. Whether they know the books or not, there’s something about the complicated nature that he has put into James Bond that has endured. Bringing it back to the books, I view this as a vote for the continuation of holding something in your hand and connecting with it. I hope that the physical world is going to continue, and things like books had better be good in order to survive. We’ve all got to try a bit harder at it, I think, to be more considered. That’s why it’s so exciting that you’re doing it yourself. You know your product and your mind enough to know when something is right or not, and you know it’s not about what’s new, but what’s true. I think that’s what people want to respond to.

Check out more of Michael’s work here and find the full range of books at our shop.