NEWS

Interview: Nicholas Shakespeare On Ian Fleming

BECOME A FLEMING INSIDER > JOIN HERE

Interview: Nicholas Shakespeare On Ian Fleming

Posted on 11 December, 2023

We sit down with Nicholas Shakespeare to learn more about his biography Ian Fleming: The Complete Man. Read on to learn about the author’s research process, how he came to write about Fleming, and of course, his favourite Bond novel…

What was the spark that started all this?

Early in 2019, I was in Tasmania, having gone there to begin work on a new novel, when I was approached by the Fleming family, who wondered if I would consider writing what would be the first authorised biography of Ian Fleming since 1966. I admit I was hesitant. Excited. Intrigued. Flattered to be asked – who wouldn’t be? But also, to start with, a bit wary, given Fleming’s fame and reputation and the amount of chaff that hedges his name. Was there anything more to say about him? And if there was, was I the person to say it? Plus, did I wish to spend four or more years in the company of a cad? I knew of Peter and his involvement in the Norway Campaign from my previous non-fiction book, Six Minutes in May – he had been the first British officer to set foot in occupied Europe in WW2. I’d grown up on Bond, yet about his creator I knew little other than tidbits picked up when making films or writing about some of his contemporaries.

How did you start your research for this project?

Before committing myself, I conducted a background check. I sought out Fleming’s two previous biographers, John Pearson – who had shared a desk at the Times Educational Supplement 66 years earlier with my father (I was able to reintroduce them) – and Andrew Lycett. I spoke to Fleming’s surviving family and friends. I was given and came across new material. And what I found as I did my due diligence was not what I expected. The image I previously had of Ian Fleming from sideways glances was in many surprising respects inaccurate and unfair. It camouflaged another Fleming, a figure who – in contrast to the “squalid, unillumined” figure of Malcolm Muggeridge’s depiction – was sympathetic, funny, vital and humane.

Did your research on this book differ to your previous projects?

With a subject as raked-over as Fleming, the challenge is to produce something fresh. As in my books Bruce Chatwin, Six Minutes in May and Priscilla, I was keen to unearth new archive material out of what has become pretty exhausted terrain. Not only that, but to scatter oral history throughout the text – e.g. first-hand accounts of those like Fleming’s step-daughter Fionn Morgan, who is one of the few who could recount lived memories.

One of my luckiest encounters was with the last surviving member of Fleming’s Intelligence-gathering unit, 30AU. So impatient was I to meet him that I arrived a Wednesday early. Later, I was glad I got the date wrong. Bill Marshall, aged 94, was hospitalised five days after our conversation. Had I come at the right time, I would never have heard what he told me. The former Royal Marine was a lightning rod directly back into the D-Day landings. He recalled meeting Fleming in northern France in 1944 and digging up the top-secret plans of a prominent German scientist.

Tell us about the title ‘The Complete Man’.

In the 1930s Fleming often spoke to the journalist Mary Pakenham of his ambition to be the Renaissance ideal, “the Complete Man”. I then read Alan Moorehead’s account of how WW2 had transformed “the ordinary man” – and how “he was, for a moment of time, a complete man, and he had this sublimity in him.” This certainly was true of Fleming: the war was the making of him (and later of Bond). Only after my book went to press did le Carré’s biographer Adam Sisman alert me to this other quote, in Raymond Chandler’s essay “The Simple Art of Murder”: “But down these mean streets a man must go who is not himself mean, who is neither tarnished nor afraid. The detective in this kind of story must be such a man. He is the hero; he is everything. He must be a complete man and a common man and yet an unusual man.”

What I like about the phrase “complete man” is that it suggests one of the central themes to have emerged: there is much more to Fleming than Bond, a character he created almost as an afterthought in the last twelve years of his life, when the most interesting part of it was essentially over. To simplify horribly, there would be no James Bond had Fleming not led the life he did, but if Bond had not existed, Fleming is someone we should still want to know about.

When memories and anecdotes differ, especially when it comes to family and also with top secret wartime stories, how do you find your way through everything and express it in a book?

So many stories disintegrate when scraped with wire wool. My favourite example is the 1997 book Op.JB, by former British intelligence agent Christopher Creighton, who argued that Fleming was personally involved in capturing Martin Bormann from Hitler’s bunker in Berlin. Taken with the story, Peter Fleming’s biographer Duff Hart-Davis agreed to ghost-write Creighton’s account. “I think (for me) the final straw came when Creighton [who also claimed to be godson of Churchill’s Intelligence expert, Desmond Morton] claimed that Fleming had brought Hitler, as well as Bormann, out of the bunker, and that on their way to the Weidendamm bridge Hitler’s head had been blown off by an incoming shell.”

When it comes to family stories as well, the truth has its own smell. I included the anecdote of Ian’s niece Gilly, that Ian had written the first Bond because of a bet with Peter, not because I felt it was necessarily 100% accurate, but because it revealed the way the family had understood things. Readers are intelligent enough to make up their own mind.

How has writing this biography changed how you think about Ian Fleming?

It struck me only recently that a moral of Fleming’s story is this: don’t run off with the wife of the proprietor of the Daily Mail if you want to avoid being forever after rendered into tabloid fat. People tend to have made up their minds about Fleming as a sardonic, wife-beating cad who strutted about pretending to be more important than he was. What decided me to write the book, after completing two months of due diligence, was to discover that his war work was indeed significant, much more than anyone had thought, although he couldn’t for security reasons talk, let alone boast about it. And how much kinder he was in life than his posthumous caricature suggested. It was Maud Russell’s line in her unpublished diary seven years after his death that clinched it: Sometimes I think of Ian – mostly of his personality, his character & his innate kindliness. (17/10/1971). Kindliness is a prize quality to uncover. I was relieved to find it in spades.

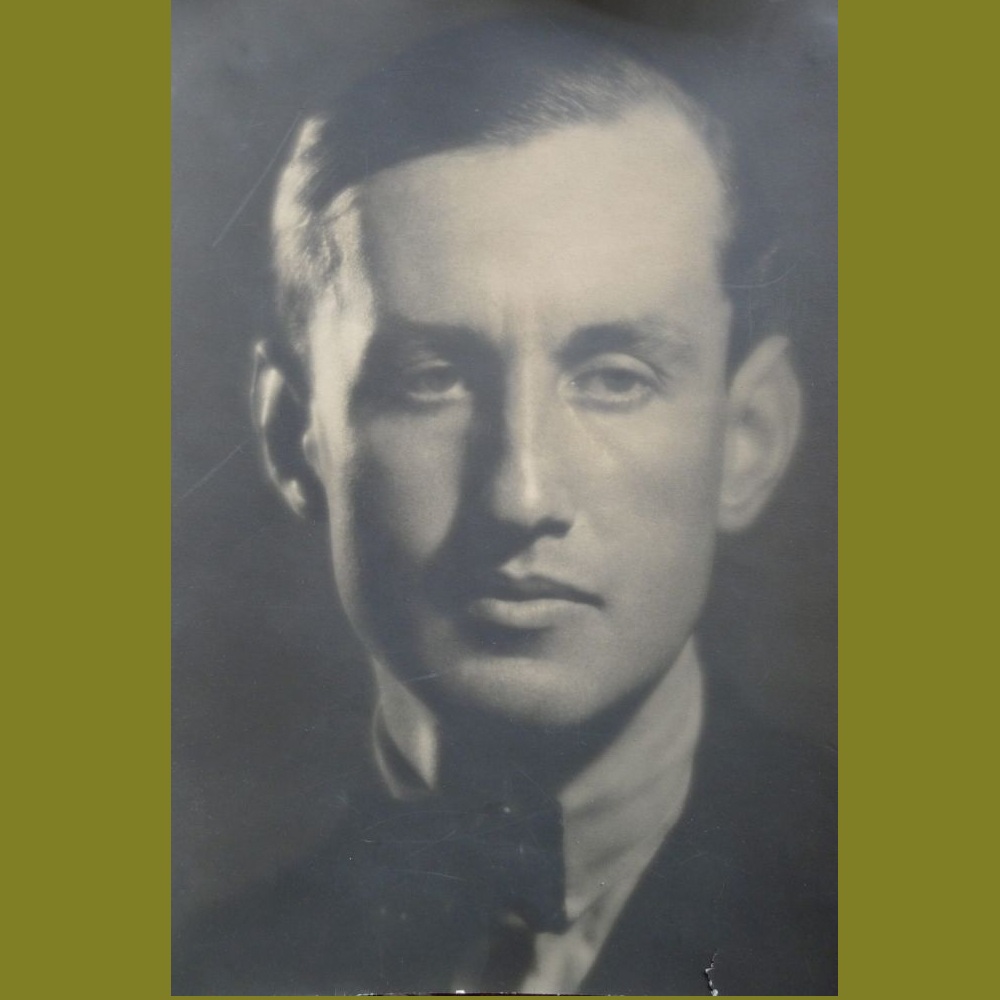

Not that he was an unprickly or an easy subject to dig up. Early on, Charles de Mestral, the son of his Swiss fiancée Monique, sent me an envelope containing the original photographs that his mother had taken of Ian in the early 1930s when they were engaged, and which she had preserved in a sort of shrine all her life. I propped up the largest photograph on my desk, I suppose as some sort of talisman; a black and white studio portrait of him c 1931. For four years, he stared impenetrably at me, defying my attempts to crack him. Only towards the end did I glance across and see Fleming through the veil of his cigarette smoke, and have a sense that I understood him better – and more than that, quite liked him. It was the opposite trajectory of my experience in writing about Bruce Chatwin, someone I had known personally and admired, but whom – because of the unnatural, up-close nature of biography – I ended up becoming less enamoured about.

How has writing this biography changed how you read and think about Bond?

That no day passes without James Bond making a media appearance is a testament to the ongoing power of his brand. Even so, I probably did not appreciate, quite, the reach of his influence. What I came to recognise is the astronomical extent of this. “He is better known than God,” Fleming’s niece Gilly told me. “All the Tibetans know of James Bond. They’ve never heard of God.” The Italian film director Adolfo Celi was welcomed with feasts in forlorn villages in Africa “where they had never seen or read anything, but where they had seen Thunderball.”

But it’s not only to foreigners that Bond has succeeded in promoting a seductive ideal of what it means to be British. He has done this most effectively to the British themselves. When we required an Ambassador to represent us at the opening of the 2012 London Olympics, who did we pluck from the heavens to act as the Queen’s bodyguard, in a cameo appearance watched by an estimated 1 billion people, but the one other Britisher to have enjoyed Her Majesty’s fame (she had attended not a few of his premieres as well).

The sun may have set on colonialist misogynists, but not on Fleming’s addictive and unmistakeable conception of a patriotic British male, attractive to both sexes, who is impossible to pay off. As a signature of Britain, Bond has proved impervious to time, to changing mores. Infinitely malleable, eternally refreshable, with his latest dialogue and behaviour contemporised by none other than Phoebe “Fleabag” Waller-Bridge, Bond is the mythical hero who not only never dies – despite earlier heart-stopping intakes of alcohol and tobacco – but who goes on getting livelier: a character with central values that still hold appeal and are adaptable enough to be reinvented over decades. As Max Hastings told me: “It seems to me that whatever reservations we all have about Ian Fleming and Bond, today it is impossible to overstate their quite extraordinary influence in making something English seem important in the twenty-first century world. James Bond has a stature to which no modern prime minister, nor royal, nor indeed anything can lay claim.”

And finally, what is your favourite 007 book and why?

My favourite 007 book is From Russia, With Love, which was also Fleming’s own favourite. I can’t do better than quote the reaction of his American publisher Al Hart: “A real wowser, a lulu, a dilly and a smasheroo. It is also a clever and above all sustained piece of legitimate craftsmanship.”

Discover Nicholas’ biography Ian Fleming: The Complete Man, at our shop.